Majestic Pele was beautiful game’s King

Tales Azzoni and Mauricio Savarese |

Pele was simply “The King.” He embraced “the beautiful game” of soccer in his 1958 World Cup debut for Brazil and never really let go.

He won a record three World Cups and was regarded unaminously as one of his sport’s greatest players – if not the best. His majestic and galvanising presence set him among the most recognisable figures in the world.

Pele died in Sao Paulo on Thursday at 82. He had undergone treatment for colon cancer since 2021.

Pele was among the game’s most prolific scorers and spent nearly two decades enchanting fans and dazzling opponents. His grace, athleticism and moves on soccer’s highest stage transfixed all sport.

He orchestrated a fast, fluid style of play that revolutionised the sport – a flair that personified Brazilian elegance on the field.

He carried his country to soccer’s heights and became a global ambassador for his sport in a journey that began on the streets of Sao Paulo state, where he would kick a sock stuffed with newspapers or rags.

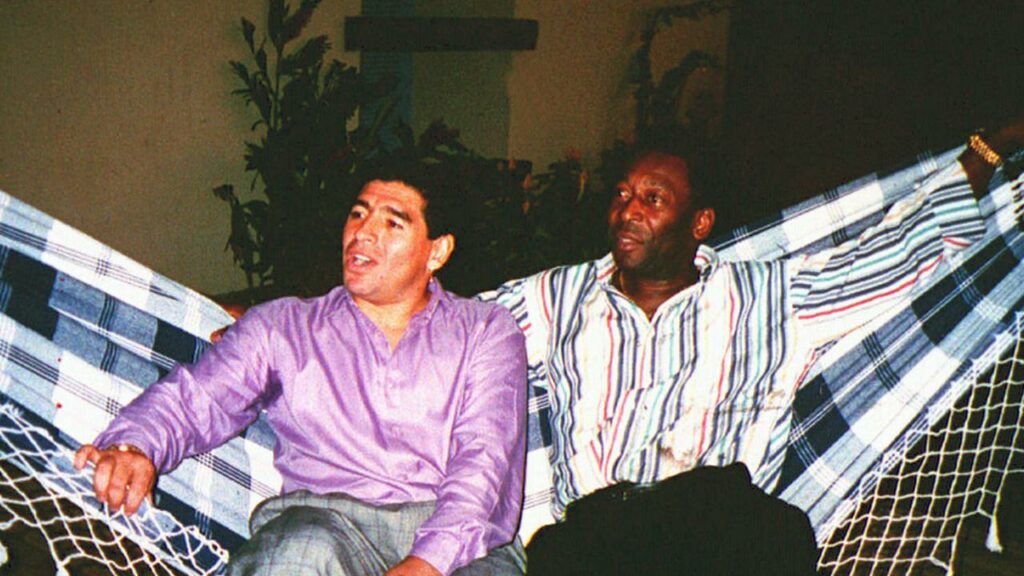

In the conversation about soccer’s greatest player, only the late Diego Maradona, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo are mentioned alongside him.

Different sources, counting different sets of games, list Pele’s goal totals anywhere between 650 (league matches) to 1281 (all senior matches, some against low-level competition).

The player who would be dubbed “The King” was introduced to the world at 17 at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, then the youngest player in tournament history.

Pele was the emblem of his country’s World Cup triumph of 1970 in Mexico. He scored in the final and set up Carlos Alberto with a nonchalant pass for the last goal in a 4-1 victory over Italy.

Pele’s fame was such that in 1967 factions of a civil war in Nigeria agreed to a brief cease-fire so he could play an exhibition match in the country.

He was knighted by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II in 1997. When Pele visited Washington to help popularise the game in North America, it was the US president who stuck out his hand first.

“You don’t need to introduce yourself because everyone knows who Pele is,” Ronald Reagan said.

Pele was Brazil’s first modern Black national hero but rarely spoke about racism in a country where the rich and powerful tend to hail from the white minority.

Opposing fans taunted Pele with monkey chants around the world.

“He said that he would never play if he had to stop every time he heard those chants,” said Angelica Basthi, one of Pele’s biographers. “He is key for Black people’s pride in Brazil, but never wanted to be a flagbearer.”

Pele’s life after soccer took many forms. He was a politician – Brazil’s Extraordinary Minister for Sport – a wealthy businessman, and an ambassador for UNESCO and the United Nations.

Pele was an ambassador for his sport, but as his health deteriorated his travels and appearances became less frequent. After needing a hip replacement, he started using a cane.

He was often seen in a wheelchair during his final years. Pele was hospitalised in 2021 for surgery to remove a tumour from his colon and soon started chemotherapy.

Born Edson Arantes do Nascimento, in the small city of Tres Coracoes in the interior of Minas Gerais state on October 23, 1940, Pele grew up shining shoes to buy his modest soccer gear.

Pele’s talent drew notice when he was 11, and a local professional player brought him to Santos’ youth squads. Despite his youth and 172cm frame he scored against grown men. He debuted with the Brazilian club at 15 in 1956, and they quickly gained worldwide recognition.

The name Pele came from him mispronouncing the name of a player called Bilé. He later became known simply as “O Rei” – The King.

Pele went to the 1958 World Cup as a reserve and became a key part of Brazil’s first championship. His first goal, flicking the ball over a defender and racing around him to volley it home, was voted as one of the best in World Cup history.

The 1966 World Cup in England was a bitter one for Pele, by then considered the world’s top player. Brazil was knocked out at the group stage and Pele, angry at fouls and hard tackles by Portugal, swore it was his last World Cup.

He changed his mind and was rejuvenated in 1970. He struck a header against England for a certain score, but the great goalkeeper Gordon Banks flipped the ball over the bar. Pele likened the astonishing save – one of the best in World Cup history – to a “salmon climbing up a waterfall.”

Later, he scored the opening goal in the final against Italy, his last World Cup match.

Pele played 114 matches with Brazil, scoring a record 95 goals – including 77 in official matches. Most of his goals came with Santos, which he led to five national titles, two Copa Libertadores trophies and two club world championships in the 1960s.

He went into semi-retirement after the 1972 season. Wealthy European clubs tried to sign him, but the Brazilian government intervened, declaring him a national treasure.

His energy, vision and imagination drove a gifted Brazilian national team, with intricate passing combinations slicing defences while leaving room for players to showcase flashy skills.

It exemplified “O Jogo Bonito” – Portuguese for “The Beautiful Game.” At its centre, like a maestro in command of his orchestra, was Pele. His 1977 autobiography, “My Life and the Beautiful Game,” made the phrase part of soccer’s lexicon.

In 1975, he joined the New York Cosmos. Although he was past his prime at 34, Pele briefly gave soccer a higher profile in North America before retiring on October 1, 1977. Among the dignitaries on hand was perhaps the only other athlete whose renown spanned the globe – Muhammad Ali.

Pele had two daughters out of wedlock and five children from his first two marriages, to Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi and Assiria Seixas Lemos. He later married businesswoman Marcia Cibele Aoki.

AP