Fused brain cells, neuron damage may explain long COVID

Samantha Lock |

COVID-19 can fuse brain cells and may explain some of the more baffling symptoms of brain fog, headaches, loss of taste and smell and other long-term neurological symptoms.

Researchers studying the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 found the virus can infect the brain and cause brain cells to fuse together and either malfunction or stop working completely.

Scientists at Macquarie University and the University of Queensland used ‘mini-brains’ infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and found it could trigger fusion in cells in both mouse and human brain tissue.

The discovery could explain chronic neurological symptoms such as headaches, ‘brain fog’, exhaustion and loss of taste or smell, even long after initial infection.

“The host brain cells are fused, possibly causing brain dysfunction,” said Professor Lars Ittner, director of the Dementia Research Centre at Macquarie University.

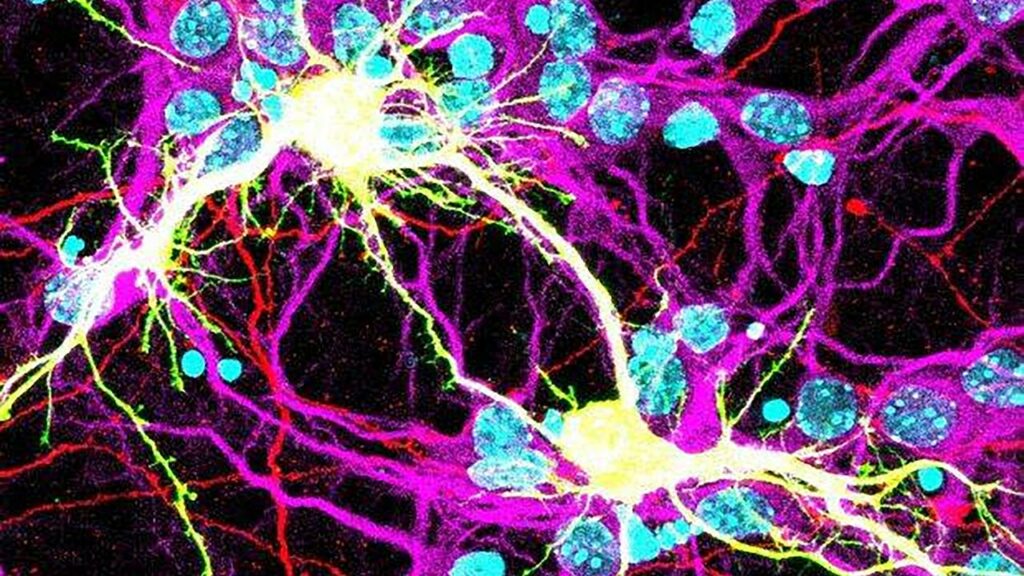

The ‘mini brains’ allow researchers to experiment on live tissue and complex human neuronal networks resembling a live human brain, bridging the gap between non-living tissue and human subjects.

“We reprogram human stem cells into brain cells, including neurons, and allow them to assemble into mini-brains in a dish,” associate professor and molecular biologist Yazi Ke said.

Some of the brains were infected with the SARS-Cov-2 virus and then compared with non-infected control brains.

Experiments showed how the viral-induced brain cell fusion occurred and documented the effects on the nervous system.

Professor Massimo Hilliard from the Queensland Brain Institute said researchers were able to observe for the first time how the spike proteins from a virus caused brain cells to fuse within 24 hours of exposure.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus particle is covered in spike proteins across its round surface and has been found in the brains of people with ‘long COVID’ months after initial infection.

Prof Hilliard said the effect of the proteins on neurons was like connecting the light switches of a kitchen and a bathroom, which was “bad news” for having both circuits functioning correctly.

“Once fusion takes place, each switch either turns on both the kitchen and bathroom lights at the same time, or neither of them,” Prof Hilliard said.

The researchers said their discovery offered a potential explanation for persistent neurological effects after infection from a range of viruses, including HIV, rabies, Japanese encephalitis, measles, herpes and Zika.

The study, published in the Science Advances journal on Wednesday, is hoped to contribute to an understanding of the long-term impact of COVID-19 infections

Prof Ittner said the team had also started a research program to understand the impact of COVID infections on the brain and how this could impact the progression, outcome and onset of dementia.

Compounds to treat COVID are also under development.

The study was a collaboration between scientists at Macquarie University, the Queensland Brain Institute, the University of Queensland and the University of Helsinki.

AAP