The passion and politics of rural medicine

Stephanie Gardiner |

Professor Dennis Pashen remembers getting ready to go diving off the Queensland coast, only to be interrupted by a labouring woman.

It happened more than once.

“You’d get the call, attach the boat, and hang around until she delivered,” Prof Pashen recalled to AAP.

“It was a bit of a nuisance, but that’s exactly what I signed up for.”

Such was the life of a young doctor in Ingham, cane farming country in north east Queensland, in 1975.

The town’s hospital had open verandahs and was “insect central”. A small team of doctors managed everything from births, to catastrophic train accident injuries, and the treatment of rare tropical diseases.

The interesting work and the embrace of the Italian migrant community kept him in the small town, 100 kilometres north of Townsville, for two decades.

“It was a warm, encouraging community. My daughter had cane farmers for godparents,” he said.

Born a “bush kid” in Cloncurry, Prof Pashen has worked in the regions for nearly five decades, most recently in Tasmania.

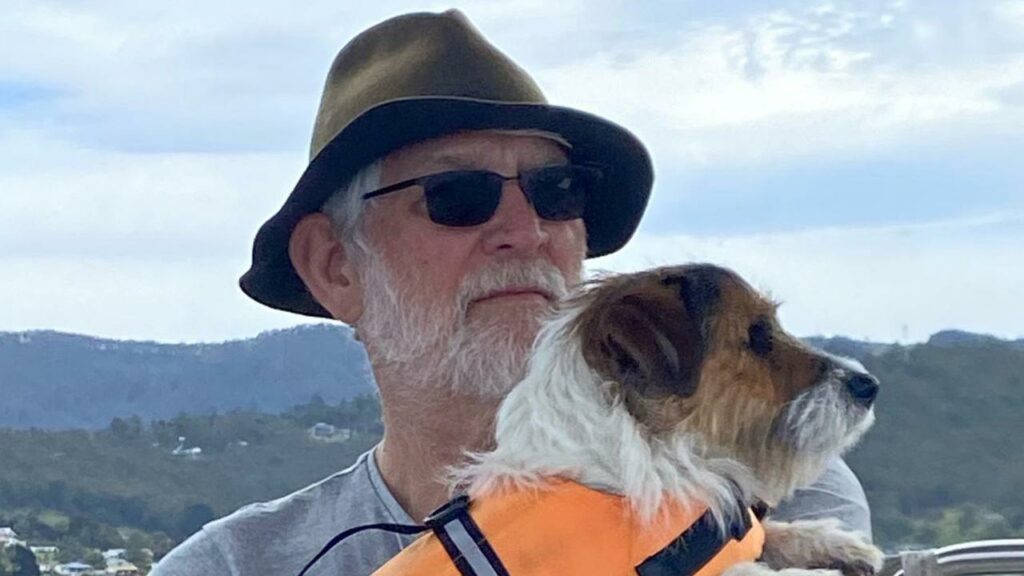

The Rural Doctors Association of Tasmania this month named him their rural doctor of the year, saying his enduring advocacy for accessible healthcare made him a national “icon”.

As federal and state parliamentary inquiries have revealed the dire state of the rural health system, Prof Pashen called on politicians to give country Australians the care they deserve.

“Rural communities are an invaluable resource for our country, and they are poorly done by, there’s fewer and fewer things to support them.”

Prof Pashen has long been on the front lines of tackling healthcare gaps in regional Australia. He ran James Cook University’s Centre for Rural and Remote Health at Mount Isa, before moving to Tasmania, where he pushed for a rural generalist training program.

He said he was continually frustrated by governments backing old, “failed” solutions.

“No one’s game to have a crack at new stuff,” he said.

“We’ve tried new things, which were well-evaluated, well-assessed, only to have them killed off by politicians, who have failed to have the courage of their convictions.”

One such idea was the introduction of physicians’ assistants, health professionals who can take on primary care and administrative duties to ease a doctor’s workload.

The program could not get off the ground in Queensland after various medical bodies resisted, concerned it was an expensive short-term solution.

The Albanese government’s move to classify more urban centres as workforce priority areas, potentially luring doctors away from the regions, only adds to other recruitment barriers like high levels of university debt, and low incomes, he said.

But he is determined to mentor young doctors into his retirement, encouraging them to find purpose in rural health.

“Communities really get behind their doctor and that’s what keeps you there.

“It can be hard, but you’re never bored.”

AAP