‘Someone’s gonna die’: fatal chopper crash probe ends

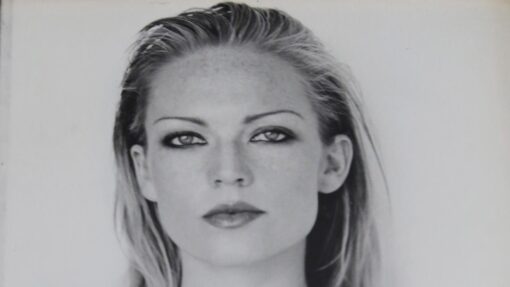

Savannah Meacham |

Not satisfied with the response to one crash, Captain Danniel Lyon offered a sobering assessment of the Australian army’s MRH-90 Taipan helicopter.

“Somebody is going to die from this,” he said.

Months later, Capt Lyon was killed along with three of his colleagues after their Taipan plunged into the sea off Queensland’s Lindeman Island.

His warning was recalled by his wife Caitland at an inquiry into the July 28, 2023 crash that also claimed the lives of Lieutenant Maxwell Nugent, Warrant Officer Class Two Joseph “Phillip” Laycock and Corporal Alexander Naggs.

The inquiry before former judge Margaret McMurdo heard Capt Lyon attended an Australian Defence Force meeting to discuss a Jervis Bay incident when a MRH-90 suffered an engine failure in March 2023, causing it to ditch into the sea.

Capt Lyon felt the issues had not been properly rectified, nor had adequate measures been put in place to prevent a similar incident from occurring.

He then offered his sadly prophetic assessment.

His wife, along with the other victims’ families, are now awaiting answers after the fatal crash inquiry concluded in Brisbane after nine hearings and dozens of witnesses over nearly two years.

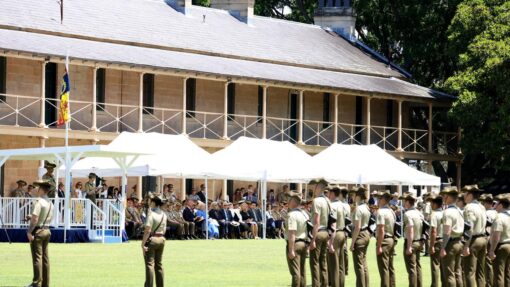

The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Inquiry was formed in October 2023, tasked with examining the cause of the crash and whether the action or inaction of army personnel or others contributed.

As the hearings unfolded, concerns emerged among army personnel about the helicopter, the severe fatigue and high workload for pilots, and over the night-vision technology they used.

A former Taipan pilot recounted being told that the aircraft had a significant risk of engine failure.

The air crew were also briefed on the risk that the MRH-90 would be inescapable if it plunged into water due to such a failure.

Crew began flying without gloves to have a better chance of removing themselves if the craft crashed into water, the ex-pilot said.

Multiple witnesses said the MRH-90 was not fit to be in service due to the engine-failure risks and high maintenance requirements.

It would later be discontinued in favour of the US-made Black Hawks.

Major General Stephen Jobson said the MRH-90 was an “immature and under-performing system” that had a high level of risk management since its acquisition in 2007.

The Army Aviation Command’s former commanding officer said he was never comfortable with the safety risk of the Taipan, but strong efforts were made to eliminate or at least minimise it.

Issues with the pilots’ TopOwl night-vision helmets were also raised, with an internal army assessment finding a fault left an “unacceptable risk”.

The assessment, made four years before the crash, found there was an “unacceptable ambiguity” with the helmet technology.

It meant there was the potential for a crash when a pilot looked away from the helicopter front windscreen or the axis at night or in difficult terrain conditions, the inquiry heard.

There were claims army aviation was dissatisfied with the assessment’s findings and wanted the software upgrade to be rolled out despite calls for further analysis.

Issues with fatigue and workload in the months leading up to the crash were also raised, with a colleague of the late air crew claiming they were working 12 to 18 hours a day on weekdays and four to six hours on weekends.

A MRH-90 pilot said the culture was becoming “toxic”, with defence headquarters not recognising the impact of fatigue or the need for time off.

In the days before the crash, which happened at the military training event Talisman Sabre, the female pilot said air crew were offered sleeping tablets after the ground trial to help them switch from day to night shifts.

She left the training exercise due to fatigue and her struggle with career pressures and a lack of progression.

The inquiry heard the final text messages she exchanged with her colleague and friend Capt Lyon.

“There is a weird vibe now you’ve gone,” Capt Lyon texted before his final flight.

“I hope you have fun tonight,” the pilot replied.

She was informed the following day there had been a fatal crash, frantically texting Capt Lyon: “F*** f*** f*** please msg me when you guys have phones.”

She never received a response.

She was one of many colleagues and family members of the deceased who broke down while giving evidence.

Capt Lyon’s wife Caitland tearily recalled the day she broke the news of his death to their son.

“I’m still haunted by the sound of our five-year-old’s screams the day that I told him daddy wasn’t coming home,” she told the final hearing.

Their daughter was just 16 months old when her father died but now cries for her daddy to come back from heaven, Ms Lyon added.

“My heart shatters knowing she has lived more days crying for daddy than she ever had laughing with him,” she said.

Lt Nugent’s partner, Chadine Whyte, spoke of how much he wanted to become a father and her feeling of devastation that he would never be able to realise that dream, urging the defence force to do better.

“While I understand that in operational environments, risk is inevitable, we must never lose sight of the fact that behind every uniform is a person, and behind every person is a family, a life and a future,” she said.

“Max’s life mattered and so does the loss of it.”

The final hearing finished on Friday with Ms McMurdo’s findings to be handed down at an undetermined date.

AAP