Libs channel Labor’s unfriendly ghost, Jim Scullin

Andrew Brown and John Kidman |

Labor coming to power after a decade of right-wing rule only to be rocked by global economic crisis, cost-of-living woes and the imposition of US tariffs.

It’s a familiar tale, right? In fact, the very circumstances that have ushered us towards the 2025 federal election?

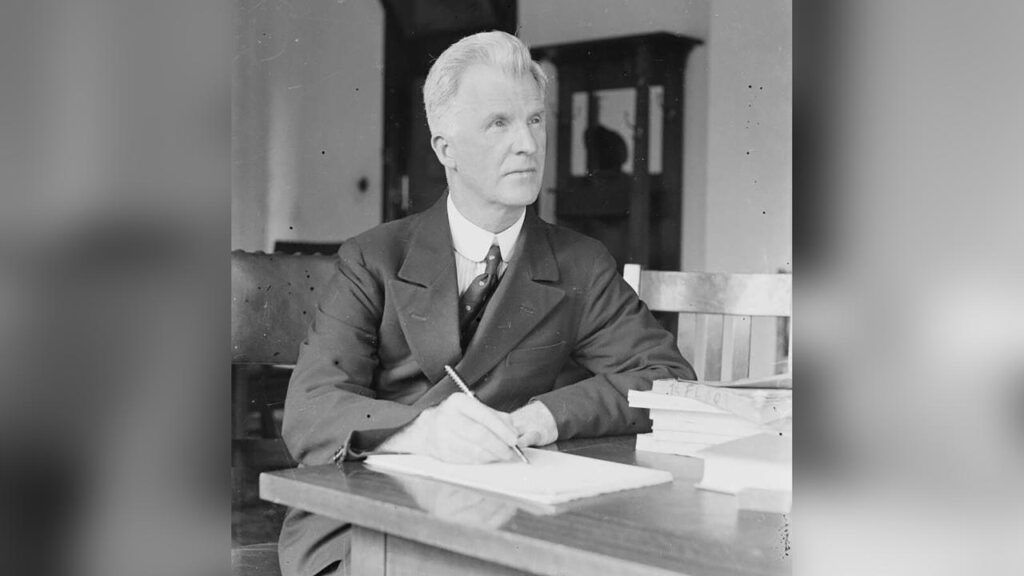

Yet it was these same events which also played out in 1931 for Labor prime minister James Scullin as he railed against the devastating impact of the Great Depression.

Potentially telling though is that despite having swept to power on a record majority, the former grocer and newspaper editor also holds the unfortunate distinction of being in charge the last time a federal government lost power after just one term in office.

It’s no coincidence Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has repeatedly referred to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on the campaign trail as presiding over Australia’s “worst government since 1931”.

History may be against the coalition winning the election after its short stint on the opposition benches but Mr Dutton hopes discontent over Australia’s economic fortunes resonates at the ballot box the same way it did almost a century ago.

Cost-of-living pressures following the Wall Street crash of 1929, just two days after Mr Scullin was sworn in, and the ensuing Great Depression were central to his demise, according to Australian National University political historian Joshua Black.

“The federal government didn’t feel it had the tools in its arsenal to respond in a way it wanted and that alienated a number of supporters,” he tells AAP.

“It was quite unpopular in the country and it was a difficult period for government.”

But economic crisis wasn’t the only factor that led to the abrupt downfall of Scullin’s administration.

The forced resignation of treasurer “Red” Ted Theodore after the Mungana affair, a fraud and dishonesty scandal linked to his Queensland mining interests, didn’t help.

Neither did defections to the fledgling United Australia Party led by Scullin’s successor Joe Lyons, which rendered him a minority leader and dependent on the volatile support of fiery demagogue Jack Lang.

A second fracture with Lang supporter Jack Beasley at the helm triggered a fatal parliamentary showdown, notable also because first lady Sarah Scullin was on hand to witness the vote. A snap poll followed, with Scullin and Labor defeated in a landslide.

While many in the present-day coalition have sought to draw a link to 1931, Dr Black says there isn’t a direct comparison as such.

“There are more obvious comparisons of the recent past, like Whitlam, and then in the 1980s in the decisions with tackling inflation,” he says.

“But I don’t think the comparison with 1931 is a useful one.

“In terms of the shambolic nature of the Scullin government itself, this term has been relatively disciplined for government messaging and ministers not leaking and staying on message.”

That said, the “rhymes of history” were apt to darken the Albanese government’s dreams, according to veteran author and journalist Graeme Dobell in 2022.

“Labor knows Whitlam’s three years in power were bedevilled by the slowing world economy, just as Jim Scullin’s Labor government was hit by the times … to be smashed by the Great Depression and party splits,” he then wrote.

“A looming global recession threatens to revisit the three-year hoodoo on Albanese.”

Even so, the current administration has undoubtedly made it its business to be around for a long time rather than a good one, as Whitlam’s crash-or-crash-through style was often accused of aspiring to.

It was a lesson learned before Albanese came to office, according to Rudd and Gillard government treasurer Wayne Swan.

“The Scullin government lacked the necessary policy tools to deal with the crisis, we did not,” he told parliament in his 2019 valedictory speech.

“While it was bullied into austerity, we would not be. We knew from the failures of the 1930s and 1990s what recessions do.”

The latter reference, Paul Keating’s “recession we had to have”, was then echoed within a year of Kevin Rudd’s first appointment in 2007 as prime minister and the arrival of the global financial crisis.

“Is it the fate of Labor governments in Australia to come to office in times of economic crisis?” politics academics Rob Manwaring and Emily Foley recently asked.

“The centre-left has long had a complex relationship with capitalism,” they noted.

“The Albanese government is again on the back foot and under intense pressure.

“In the current era, voters are punishing incumbents and the economic gods certainly enjoy playing with Labor governments.”

But history shows voters often like to give first-term governments the benefit of the doubt, Dr Black says.

It’s why oppositions aren’t so readily returned to office.

There’s also the fact winning from opposition remains a challenging prospect so soon after an election loss, he says.

“There’s kind of a political pain oppositions experience after losing government, there’s a difficult adjustment to make,” he adds.

“Political parties get comfortable with the trappings of power and they have to learn to live without and have less resources and money and less natural access to the media.

“The difficulty of reorientating decisions and learning from mistakes of the past makes it so difficult for oppositions to win government on first go.”

AAP